Identifying Rural Viral Hotspots Before They Explode

New York has been the epicenter for COVID-19 cases in the United States, but the virus poses dire problems in rural America as well, where access to healthcare is sparse and an outbreak could overwhelm already limited resources.

The New York Times reports that more than two-thirds of rural counties across the nation had confirmed at least one case by early April, and an op-ed in the Times says that the Rural South is the perfect storm for a COVID-19 disaster.

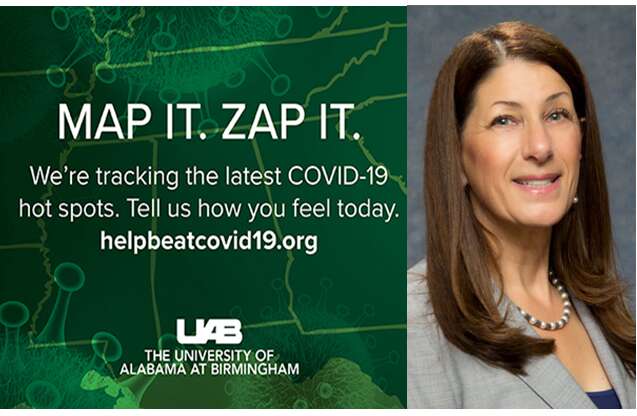

Sue Feldman (MA, ’07; PhD, ’11, Education, and Information Systems & Technology) is part of a team of experts at the University of Alabama at Birmingham that has devised an online symptom tracker to identify potential coronavirus hot spots in the rural Deep South, providing valuable information to public health officials as cases emerge.

Tracking symptoms as they emerge to identify potential hot spots in rural parts of the Deep South.

“We’re trying to keep emergency departments from becoming inundated,” she says.

Their website, HelpBeatCOVID19.org, invites residents to report their health daily by answering a survey that takes 10 to 90 seconds to complete, depending on symptoms. The first question asks, “Tell us how you feel today,” to which a choice is given between “I feel good” and “I feel sick.” How someone responds triggers its own set of follow-ups.

“We are taking a look at COVID-19 symptoms alongside underlying medical conditions to provide public health officials an in-depth analysis of how rural areas are affected in real time,” says Feldman, associate professor at the university’s School of Health Professions and School of Medicine. “You might not have any symptoms, and then you may start with a fever, and then you may add a cough. What we’re hoping to do is to track the symptoms as they emerge to identify hot spots that normally would be very difficult to identify.”

The survey, which maps responses by ZIP code, also takes into account economic and social factors that may be keys in understanding an area’s vulnerability.

As of April 14, nearly 20,000 people had shared their health status. Since not everyone in the region has internet access, the university is also gathering data via text message and an 800 number.

“It’s important to look at surveillance and spread—two sides of the same coin. We are looking at things from a surveillance perspective, which gives you an element of knowledge to deal with the emergence of spread. You lose that once you already know where the disease is,” Feldman says.