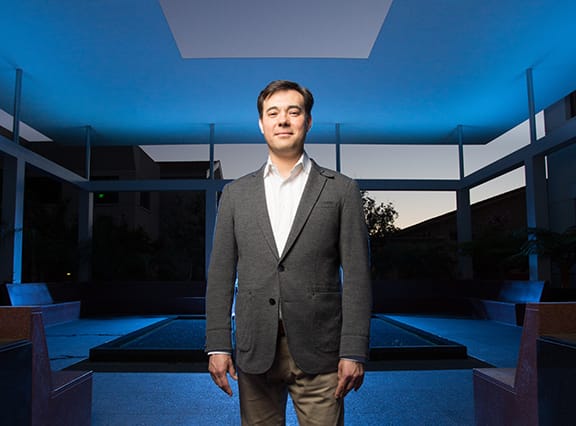

Jeremy Hunter: Why Mindfulness Matters

Business Managers Can Manage Themselves by Tapping Buddhist Concepts

In the fifth or sixth century BCE, Buddhist texts extolled the power of being “awake, aware, mindful,” declaring, “a tamed mind brings happiness.”

In his 1968 book, The Age of Discontinuity, theorist and educator Peter F. Drucker, considered the father of modern management, wrote about the virtues of “trained perception” and “disciplined emotion.”

Respective of its ancient and modern contexts, mindfulness—the concept of deliberately directing one’s attention—is what Jeremy Hunter has been teaching for more than a decade as assistant professor of practice at CGU’s Peter F. Drucker & Masatoshi Ito Graduate School of Management. Mindfulness is significant, he said, because it “enhances clarity, focus, and judgment; enables more skillful decision-making; improves communication and interpersonal relationships; and fosters greater quality of life.”

Over the past few decades, science, higher education, and the corporate sector have aligned with what Buddhist practitioners have been saying (and what Hunter has been teaching) all along: Becoming more aware of ourselves and being in the “here-and-now” can lead to transformative experiences and positive changes.

“Our lives are full of actions, and those actions bring about results,” Hunter said. “Are those results ones we want or do they cause us or others suffering? Oftentimes, because humans largely run on automatic pilot, we don’t know how we got that result. Sometimes we know how we got a result but we can’t control what happened to bring that result into being. Mindfulness helps you change the result.”

When applied to the worlds of business and leadership, those results can prove critical: the power—borrowing Drucker’s terms—to manage oneself.

“A Tool Kit”

The benefits of mindfulness were first articulated about 2,500 years ago. The Dhammapada, a collection of ancient Buddhist texts, read, “It is good to control the mind, which is difficult to restrain, fickle, and wandering.” The texts also state, “By awakening, by awareness, by restraint and control, the wise may make for oneself an island which no flood can overwhelm.”

“Right mindfulness” is traditionally part of the Eightfold Path that leads to wisdom and enlightenment according to Buddhist teachings. Within this framework, early practitioners employed meditation, breathing exercises, chanting, and other contemplative practices to discipline their mind and focus their attention.

Other, later thinkers trod similar ground. Eighteenth-century philosopher Adam Smith wrote about an “impartial spectator,” the concept of a calm, detached point of view that, through self-reflection and control, could be used to determine moral decisions. Nineteenth-century thinker and psychologist William James extolled the virtue of directing our attention and exerting control over our minds as “the root of judgment, character, and will.”

According to Hunter, what Buddhism brings to the table are methods and tools.

“The West has had the idea of the ‘impartial spectator’ but it didn’t have systematic tools for cultivating it,” he said. “Even William James said that bringing back a wandering attention was the key to self-mastery, but quickly lamented there weren’t practical tools to bring it about. Buddhism offers a tool kit.”

But Buddhist ideas were largely unknown to Westerners until the latter half of the twentieth century. During the 1960s and 1970s, as the Apollo missions were rocketing into outer space, other Americans journeyed to India, Japan, and Southeast Asia as “explorers of inner space,” Hunter said.

These “explorers” include Daniel Goleman, a psychologist, two-time Pulitzer Prize nominee, influential business thinker, and author (Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ); and Richard Davidson, a distinguished neuroscientist, director of the Waisman Laboratory for Brain Imaging and Behavior at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and an expert on the impact of meditation on the brain. Both received their PhDs from Harvard University and spent several years in India and Sri Lanka during the 1970s studying Buddhist thought, methods, and practices.

“They wanted to understand what [Eastern] cultures and traditions had to offer us,” Hunter said. “They were disillusioned by a materialistic West. So they traveled East, studied with a variety of teachers and brought their lessons back here.”

Eventually, these “explorers” became the professionals, scientists, researchers, writers, and journalists of their generation. Via their work and studies, they began disseminating Buddhist concepts through Western culture over the next few decades.

Modern science and medicine took notice.

Brain Redesign

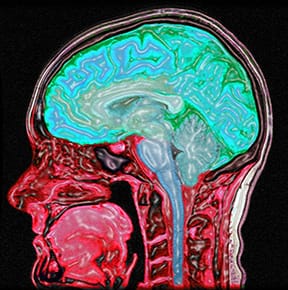

Up until the 1960s, most researchers believed that the only major changes that could take place in the brain occurred during infancy and childhood. At that point, the brain’s structure—it was believed—became permanent.

However, an enormous amount of research now shows that this is far from the case. In fact, experiments show that the brain is able to change and adapt over a lifetime. It’s a concept known as neuroplasticity.

Neuroplasticity research shows that experiences—such as those guided by mindfulness principles—can reorganize pathways in the brain and lead to long-lasting, functional changes. Essentially, the brain has the ability to redesign itself.

“Suddenly the idea that what a person practices could transform their mind became not only worthy of scientific study but it has actually been scientifically studied, and the data has been incredible,” Hunter said.

For example, researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital were able to demonstrate changes in areas of the brain associated with memory, self-awareness, and compassion after subjects underwent eight weeks of mindfulness meditation, according to a 2011 report in Psychiatry Research. Mindfulness training improved subjects’ ability to focus, reduced their stress, anxiety, and symptoms of depression, and improved emotional well-being, according to a 2012 paper in The Journal of Neuroscience.

Science had finally become enlightened, echoing what the Buddha and those who came after him taught centuries before: Mindfulness can help us re-sculpt our perception so we see things clearly and objectively.

It is this clarity and objectivity that are essential to good management.

Educating Attention

Good management, according to Drucker’s philosophy, is key to a healthy, flourishing society. And good management originates with managers who have learned to manage themselves before they manage anything else.

“Most of what we call ‘education’ in the West is about educating your rational mind, about educating a person to think better,” Hunter said. “But Drucker wrote a great deal about how we have overtrained people to think and undertrained them to see. And one thing we don’t see is ourselves in action. If we had a better view of that, we would have a better understanding of what we are actually doing and what the impact is of what we are doing.”

Unfocused, inattentive managers are prone to making decisions out of fear or anger that lead to wasteful and unwanted results. Focused, attentive managers—those who regulate their emotions and reactions in the face of change and challenge—prompt wiser choices and more productive results.

These are the ideas Hunter has been teaching to students for more than a decade.

Hunter—who holds a PhD in human development from the University of Chicago—leads his students through a 15-minute meditation session at the beginning of a class session. “It helps to ground people who may have had a frenetic day,” he said. “So many of us run around in a half-frenzied state. Simply taking a moment to let attention rest in the present leads to a more focused, productive conversation.”

Hunter has taken his students to Dividing the Light, a “Skyspace” created by CGU alumnus and internationally renowned artist James Turrell (MFA, 1973) that was built on the Pomona College campus. Turrell’s work aims to show people they are creating their own reality. Dividing the Light is a pavilion open to the sky through a specially-designed aperture in the roof. However, at first glance it is not apparent whether there is an actual opening to the sky or a glowing painting on the ceiling. The space challenges visitors’ notions of what is real. Lights programmed to coincide with sunset and sunrise transform the awareness of color. It shows viewers that their perceptions are far more malleable than they realize.

Transforming perception of what is real is a central theme of Hunter’s classes.

“My classes [at CGU], ‘The Executive Mind’ and ‘The Practice of Self Management,’ are not about reducing stress or zoning out,” Hunter explained. “Mindfulness and self-management are strategic tools. They help people see themselves clearly, and also help people see reality undistorted by their own emotions and biases. Only then can they make effective decisions to meet that reality.”

Hunter’s students have met such realities head-on.

Creating Choices

One former student who held a leadership role worked in a department that was “perennially at war” with another department. Mindfulness allowed her to become aware of the root of the problem: It was she who was harboring resentment, judgment, and anger toward the other department.

“Not only had she created the situation in her mind, but through this mindset she had perpetuated it and spread it,” Hunter explained. “And the difficulty between the two departments was entirely her own doing. That was an incredibly humbling moment for her.”

This moment of awareness prompted her to turn things around. She ended up explaining this—and apologizing—to the other department.

“It took some time, but they reworked the relationship,” Hunter said. “Last I heard, they both kind of teamed up to deal with another department they had difficulty with.”

In another case, Mark Dust, a veteran of Iraq who was suffering from post-traumatic stress syndrome, learned to manage his condition and find healing through the methods he learned in Hunter’s “The Executive Mind” class. Dust has since completed an executive MBA through Drucker and is currently enrolled in a PhD program in CGU’s School of Community and Global Health.

“If I take my students’ feedback from the last 12 years, what they frequently say is, ‘These tools helped me to create choices. I was able to create choices where I didn’t see or even think choices were possible,’” Hunter explained.

Not surprisingly, Drucker students have voted him Professor of the Year four times.

Mindfulness in Action

In the article “Is Mindfulness Good for Business?” Hunter wrote for the April 2013 premiere issue of Mindful magazine, he offered a number of methods to cultivate mindfulness in the workplace:

• If you feel distracted, practice following a simple object or process (like breathing). This helps with focus. “Your attention wavers less and you’re not as easily pulled away by external distractions or internal chatter,” Hunter wrote.

• If office gossip and politics are making work difficult, listen to your co-workers and “consider what might cause them pain.” But don’t judge.

• If you’re physically tired, Hunter’s article suggested you “take a few minutes and let your attention scan your whole body from toe to head” to cultivate more body awareness.

Over the past decade, universities, the corporate world, and mainstream media have latched on to the concept.

In 2004, UCLA established a Mindfulness Awareness Research Center. Harvard Business School Professor William W. George led a mindful-leadership conference with a Tibetan Buddhist meditation master in 2010 and considers self-awareness central to good leadership. High-level companies such as Google have hired or made use of mindfulness experts.

The February 2014 issue of Time magazine declared “The Mindful Revolution” on the cover, citing the “Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, Fortune 500 titans, Pentagon chiefs,” and others who promote its methods.

“Mindfulness frees us from our habitual, obsessive tendencies to play out emotionally reactive patterns of action over and over again,” Hunter said. “Mindfulness is like a clutch that decouples our minds from that crazy hamster wheel spinning in our heads. Mindfulness creates freedom and possibility to choose new and more positive ways of acting in the world. From what I can see, the world needs it.”

More than two decades ago, Hunter needed it, too.

Deep Roots

Hunter’s work is also informed by personal experience, which he candidly spoke of at a 2013 TEDx Orange Coast event.

In the early 1990s, he was diagnosed with an auto-immune disease. Hunter’s doctor told him there was no effective treatment, no cure . . . and it was likely to be terminal due to organ failure within five years.

Around 1992, the then-20-year-old Hunter, a sophomore at Wittenberg University in Ohio (where he received his bachelor’s degree in East Asian studies), encountered the book The Three Pillars of Zen. It was a gift from one of his religion professors at Wittenberg. The book, written by a Nuremburg Trial court reporter-turned-Zen teacher named Philip Kapleau, was published in 1965 and is considered one of the early books in English to present Buddhism as a pragmatic way of living as opposed to a rarefied or abstract philosophy.

The Three Pillars of Zen was “one of the first books to teach a Westerner how you actually do Zen practice and included very basic meditation instructions,” Hunter said in a 2010 online interview with The Potential Project, a Denmark-based organization that offers corporate-based mindfulness training around the world. “So, quite regularly I did this practice over and over again for years, every night before going to bed.”

Hunter credits this practice with dramatically slowing down the progress of the disease.

Slowing down, but not stopping.

Sixteen years after his original diagnosis, lab results showed him the implacable truth: He was dying. His doctors recommended life-saving surgery, a kidney transplant. But that presented a problem—having to ask for help from prospective organ donors. That “was like throwing a birthday party with a secret fear that no one was going to show up,” he told TEDx attendees.

Again, Hunter employed the practices he had promoted for so long. He directed his attention to face his own “fear, pride, and vulnerability” to survive the ordeal. In the end, 25 people—more than a dozen of them his former students—stepped forward as organ donors. One student, Drucker alumna Laura Newman, ended up a positive match.

“For me, mindfulness is not a hobby, fad, or something that I picked up in a weekend workshop,” Hunter said. “Disclosing the experience of illness and facing my own mortality lets people know that I had to deal with difficult things just like they’ve had to deal with difficult things. If I were to stand up and say, ‘Do these practices because they’re good for you,’ who would listen to that? I share that part about myself because I had to do all the things my students are asked to do.”

Hunter’s experiences—both professional and personal—have been enlightening.

“I am still very much a learner on this journey.”

To download and read two of Jeremy Hunter’s latest papers, click on the links below:

“Focus is Power: Effectively Treating Executive Attention Deficit Disorder”