David Sing: Educating Hawaii’s Talented—and Underserved—Schoolchildren

Growing up as a native Hawaiian allowed David Sing (PhD, Education, 1986) to experience firsthand the shortcomings of his state’s educational system.

Hawaii’s curriculum failed to take into account Hawaiian values and perspectives. Local history and language weren’t factored into studies and lesson plans. Without a connection between culture and classroom, native Hawaiian students—those descended from the islands’ original Polynesian settlers—struggled

In response, Sing designed a program that recognizes the potential and promise of all students. But it also integrates Hawaiian culture and perspective into its instruction, creating optimal learning conditions for native students.

Twenty-five years later, Sing’s Nā Pua No‘eau Center for Gifted and Talented Native Hawaiian Children at the University of Hawaii at Hilo (UHH) serves as a model for improving academic achievement and raising aspirations of Hawaiian and other underserved children.

Sing credits theories he learned at CGU for helping him shape the center he led as its executive director since 1989. In particular, he cites a theoretical model that recognizes the significance of matching teaching strategies with the socio-cultural background of students.

“The diverse populations that exist in America have distinct needs, distinct interests, and learn differently,” said Sing, who retired last year from UHH. “The model is intended to try to have strategies that attend to those distinctions.”

When Sing started Nā Pua No‘eau at UHH through a grant from the U.S. Department of Education, the goal was to identify talented students with professional and academic potential yet measured low on standardized testing and in the classroom. In order to create a passion for learning with these students, the center—which serves as a supplement to and not a replacement of Hawaii’s educational system—promotes learning strategies that feature real-life situations and concepts relevant to Hawaiian identity. For instance, when teaching astronomy and marine science, students would be engaged in learning how to voyage on a traditional Hawaiian sailing canoe, Sing said.

“The education is built into real-life situations that come from a historical and environmental situation that they presently are involved . . . students are understanding the application of science and mathematics, so when they go to regular school it all clicks for them,” he said.

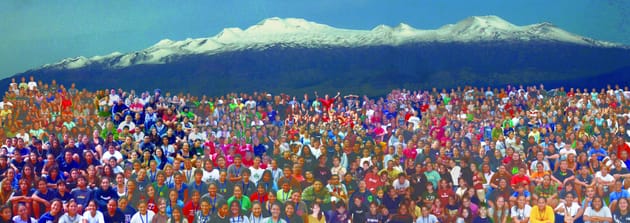

Under Sing’s leadership, Nā Pua No‘eau outreach centers were established across the state, on the islands of Maui, Kauai, Oahu, Molokai, Lanai, and Hawaii. His learning models have been replicated throughout other native and underserved communities on the mainland and internationally. The center has served more than 16,000 students, according to Sing.

Sing has been recognized for his efforts. In 2008, he received the National Indian Education Association Educator of the Year Award. He was awarded the 2009 Native Hawaiian Education Award, which also honored him as educator of the year.

Because Nā Pua No‘eau emphasizes creating a pathway to different professions, hundreds of native Hawaiian students have gone on to professions that serve the state and its communities. Students have ended up as medical doctors, lawyers, teachers, natural environment managers, community leaders, geologists, and marine scientists, as well as University of Hawaii faculty and staff.

“The pathway is to increase the number of professionals that return and serve their native Hawaiian communities and to be role models for future generations,” Sing said.