Prof. Lori Anne Ferrell and the Art of Destruction

School of Arts & Humanities Professor Lori Anne Ferrell has uncovered that scrapbooking is more than just a hobby or a means of preserving memories.

The practice of cutting and pasting has been around a lot longer; for centuries, in fact. Ferrell and her co-curator, Stephen Tabor, reveal this in the exhibition, “Illuminated Palaces,” that was on display at the Huntington Library through October 28.

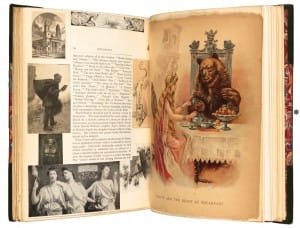

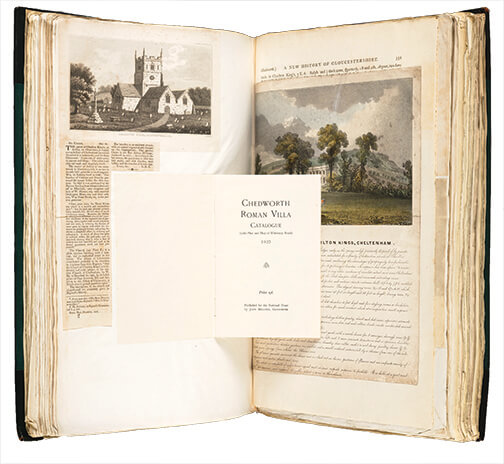

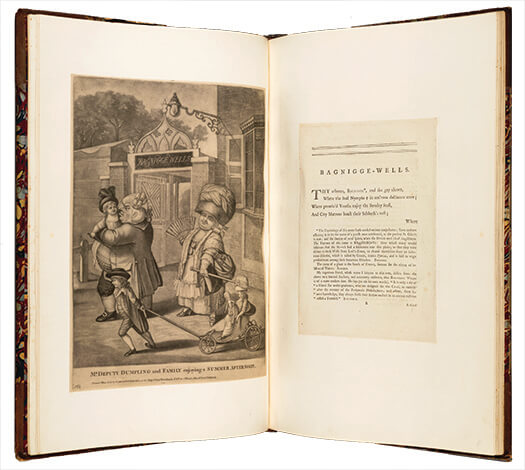

Extra-illustrated books, as they are called, thrived in the eighteenth century as a way for wealthy collectors to expand already-published works with additional artwork or prints. Essentially, people would find a print, piece of artwork, letter, or other piece of memorabilia that was relevant to the text at hand, inlay it in the original text, and then rebind the pages.

“Extra-illustrated books are perhaps akin today to collecting baseball cards, except this was practiced at a much higher level,” said Ferrell. “You would have a book of interest—for example, history, Shakespeare, the Bible, geographies, or travel books—and you might have collected pictures or engravings that would speak to the story that is on the page. Then you would personalize and expand the original book with those pieces.”

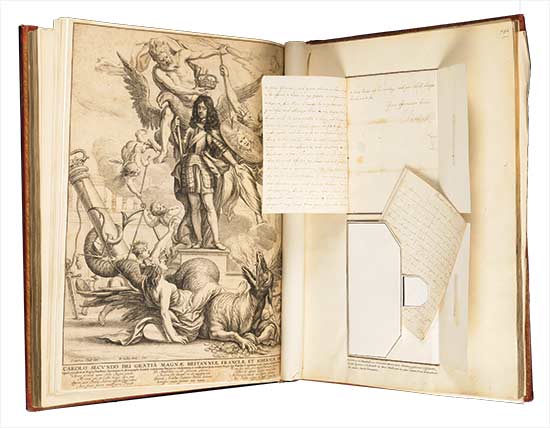

The practice actually began earlier than the hobby of the later 1700s, possibly originating in religious dissent. Members of the newly reformed Church of England, for example, might paste devotional prints into their Bibles to hide their loyalties to the Catholic Church. These “crypto-Catholics” would appear to be reading the Bible, when they were actually meditating on a print of the Virgin Mary or a traditional saint tucked inside.

A British clergyman named James Granger popularized the practice with his Biographical History of England, from Egbert the Great to the Revolution. Published in 1769, the book catalogued portrait prints found in the print stalls of London and Europe, dividing them into 12 classes: monarchs were in the first class, aristocrats in the second, women were in the eleventh, and infamous people—known only for doing one thing—in class 12. Like “‘The Mighty Eater,’ who once ate more sausages than anyone else at the fair and was immortalized in a broadside pamphlet,” Ferrell joked.

This collection of prints not only started an upper-class craze, the practice also adopted Granger’s name—it is now often referred to as “Grangerizing.” While it was itself a destructive art form, Granger’s dictionary was a way for England to reconstitute class and boundaries in a tumultuous society. According to Ferrell, it symbolized a reimposition of order after a turbulent period of civil war and interregnum in seventeenth-century England.

Granger’s dictionary inspired another important work: the “Kitto Bible,” currently housed at the Huntington Library and considered the largest Bible in the world. The extra-illustrator of this Bible managed to find 33,000 illustrations and prints to add to it, expanding the original two-volume set to 60 extra-large folio volumes, each weighing 25 to 30 pounds apiece.

This Bible provides an interesting insight into the way that eighteenth- and nineteenth-century readers approached the sacred text. The Kitto Bible has a particular significance in the history of the book and religious studies that goes beyond being merely the largest of its kind.

“Biblical scholars are always interested in how people read their Bibles. This really fixes a moment in time. James Gibbs (the illustrator) was an extremely meticulous Grangerizer, and he would often underline the text that he planned to extra-illustrate. This allows today’s reader to follow his thought process,” Ferrell said. “It is a unique view into one nineteenth-century man’s interactive practice of Bible reading, which—by its very nature—requires creative approaches from its readers.”

Despite the significance of the Kitto Bible in religious studies and the wealth of knowledge it provides about the culture of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Grangerizing process was, and still is, controversial. The practice of destroying books is simply beyond the pale, a view held by co-curator Tabor, curator of early printed books at the Huntington Library.

Ferrell, however, is often more interested in the cultural significance that extra-illustrated books provide—a telescope of sorts into eighteenth- and nineteenth-century thought.

“Stephen’s sense of what was done to these books often focused on the incredible destruction. Some hobbies, when followed too strongly, become both decadent and destructive—like pinning butterflies to a wall,” said Ferrell. “My reaction was closer to, ‘Can you believe what people do!’ And, to what lengths they will go to communicate their ideas.”

Ferrell and Tabor walked a thin line navigating the controversy of extra-illustrated books. As part of the promotional media for the exhibit, they released a video showing how to inlay a print into a book, but it comes with a warning label: do not try this at home. “We had to soul search and choose a bad, cheap print from a used bookstore that we didn’t mind cutting,” Ferrell said. “Actually, we didn’t even want to do that.”

Not all are so hesitant.

Today, people repurpose old books for art’s sake into several media: jewelry, bookmarks, and even as canvassing for original artwork. “There’s a guilt factor in seeing books as expendable; there’s a billion paperbacks. And how many of them do you drop into the tub?” laughed Ferrell.

Despite the destructive act involved in creating these books, a wealth of information lies between the pages. During the two years that Ferrell and Tabor worked on curating the show, they found several letters from famous eighteenth- and nineteenth-century figures, including original letters from President George Washington and King Charles II, both of which are featured in the exhibit.

“And those were only the ones that made it in!” Ferrell said. “We got sort of blasé at the end. I would shout from one end of the stacks, ‘Never mind; it’s just another letter from Lord Byron!’”

While the exhibit is bursting with finds, two years worth of work was not enough to tackle all the extra-illustrated books that the Huntington Library has in its stacks.

The Huntington’s collection of extra-illustrated books is still not fully catalogued, and extra-illustrated books alone account for more than 90 percent of the Huntington’s artwork holdings. At the turn of the century, collectors bought the books thinking they would be important, but they fell out of scholarly favor by the mid-twentieth century and, according to Ferrell, now sit collecting dust.

“It would take decades and a team of researchers to catalogue them all,” she said.

Extra-illustrated books declined in popularity with the Great Depression and World War II. Additionally, because it became more accessible to the lower classes, it was no longer elite. Ready-made kits for the preservation of war memorabilia combined with the decline of the print market contributed to the waning interest in extra-illustrating books after the nineteenth century.

Recently, however, extra-illustrated books proved likely to be both valuable and interesting for scholars and the public alike. The current exhibition was inspired by another exhibit that Ferrell helped curate in 2005. It included the Kitto Bible, which uncovered an original watercolor by William Blake, among other rare finds, and the curators decided to give it a room to itself in the exhibit.

“We had a specially made bookcase so we could include all 60 volumes. And people loved it. When I realized this was its own genre, I wanted to focus an exhibit on it,” said Ferrell. “I badgered Stephen a bit—but it didn’t take much badgering. We think these things are incredible.”

Ferrell believes the idea of extra-illustration remains relevant as the modern world undergoes another major change in book technology. With an emerging digital culture that consistently bombards the senses with visual and intellectual information, and as books and newspapers become digitized, the value of print on the page is declining.

“Will there just be these precious volumes that we will pull out one day and admire for their quaintness?” Ferrell queried.

Regardless of the rise and fall in popularity of extra-illustrated books, their recent debut at the Huntington Library has Ferrell remaining certain about their place in history and optimistic about their value to future scholars.

“I only wish I’d had my hands on this for some projects I’ve done in the past,” she said. “I’d love to have known what eighteenth-century readers thought about seventeenth-century history. Part of what could give me a clue is what pictures they selected to illustrate their history books.”

It also has inspired Ferrell to look into a new area of study concerned with botanical prints Grangerized in collections of Shakespeare. “The nineteenth century was crazy about botanicals. For example, in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, someone would see the reference to eglantine (a flower) and then go out and buy all the botanical pictures of the plant that they could, and then inlay them in the book,” she said.

Because extra-illustrated books have lacked attention until very recently, Ferrell is sure that they will take off in contemporary scholarship and research. Now that researchers—Ferrell among them—have realized that Grangerized works included handwritten letters and original artwork, she is sure that the area of study is going to expand.

“I’d love it if students could see what a remarkable research trove this could be,” Ferrell said. “I can’t imagine why anyone studying British literature wouldn’t want to get their hands on this stuff. I believe that these ‘mutilated’ books can create a new understanding of our history, book history, and the history of reading and reader response—and that is relevant to our studies in the humanities.”

Below is video footage used for the “Illuminated Palaces” exhibition. (Courtesy of The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens)