Father Giovanni Esti Finds Faith in Social Development

Motivated by a Mission

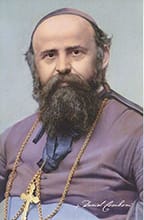

A Catholic missionary working in Cairo since 2007, Father Giovanni Esti saw revolution unfold before his eyes. The CGU alumnus (PhD, Religion, 2008) founded a social development center in the heart of the Egyptian capital. The center, Markaz Comboni in Arabic, is walking distance from Tahrir Square, the focal point for the demonstrations that gripped the country in 2011 and 2013.

It proved a unique vantage point.

The Italian-born priest established the center in 2010 to provide training and education to local youth. But political changes Esti witnessed first-hand over the past three years also underscored his efforts to promote interfaith trust, community empowerment, and dialogue among his neighbors.

“We try to be people that mediate,” he said. “We do workshops, congresses. We want to create a space where people can talk about social development, nonviolence, and women’s rights.”

Esti, 50, credits CGU for awakening a passion for the study of Christian origins. But he credits his experiences in Egypt and elsewhere—helping to rebuild a homeless shelter in a poor Los Angeles County neighborhood—for renewing his faith in the power of social development.

Rebuilding a Shelter

After studying at the Catholic Theological Union in Chicago to become a priest and receiving master’s degrees in theology and divinity, Esti was assigned to Southern California and came to work at Our Lady of Guadalupe in Irwindale in 1991. Just a few miles away in Azusa, he noticed a rundown homeless shelter that was struggling to keep its doors open.

The Peregrinos De Emaus Homeless Shelter—affiliated with the St. Francis of Rome Catholic Church in Azusa—provided employment, medical, and psychological referrals, as well as food, clothing, bus tokens, and temporary lodging. It was a place where poor immigrants and those grappling with drug addiction and mental illness could find treatment, religious instruction, and “some sense of dignity,” Esti said.

But by 1994, the shelter faced demolition because of numerous code violations and a lack of money. So Esti stepped in. Working with city officials and community groups, the priest helped to identify private donors, raise money, and reorganize the center’s management. Eventually, the center was rebuilt and reopened.

“Upheaval and Change”

After about 10 years in California, Esti enrolled at CGU to pursue a PhD and study at the university’s then-Institute for Antiquity and Christianity. He studied under the guidance of Professor Emeriti James M. Robinson, a world-recognized expert on religious texts who edited and translated the collection of apocryphal scriptures known as the Nag Hammadi Library or codices.

“[My professors] challenged my views and broadened my reading of Christian origins,” Esti said.

The priest said his program’s historical approach to studying Christianity opened his mind to the way he understood his faith and fueled an interest in its origins.

After receiving his PhD, Esti decided to move to Cairo to continue his research, specifically to study Coptic Christianity and the ancient Coptic language. Esti’s biblical research continues today at the Evangelical Theological Seminary in Cairo, under the guidance of Atef M. Gendy, the seminary’s president and professor of New Testament studies.

“When I came to Egypt, I was mostly motivated by academic, intellectual interest,” he said. “Of course, I was thrown into a country that was about to explode into revolution and a great deal of upheaval and change.”

Building a Center

When he arrived in Cairo in 2007, the first challenge Esti faced was learning the language. He spent two years studying Arabic as he worked at the Church of Cordi Jesus Sacrum, founded by St. Daniel Comboni (see “St. Daniel Comboni” sidebar below).

Esti said he also faced difficulties associated with being a religious minority in country where Islam is the state religion.

“Since religion was so divisive, I preferred to get involved in something that would serve as common ground, where both Christians and Muslims could encounter each other, and that was in the field of social development,” he said.

Esti convinced his superiors to refurbish the foyer of an adjacent church into what would become the Markaz Comboni. He hired a staff of four for the center who taught crafts, the arts, leadership, grant-writing as well as web and graphic design.

“I realized that if I wanted to do something, I had to empower people,” he said.

He did this through “micro projects,” Esti said. The center purchased six acres of land near Wadi el Natrun, a desert area near the Nile Delta. Through the use of solar panels and biogas technology, the land is being transformed from sand into fertile soil.

The Process of Change

The center’s proximity to the physical epicenter of Egypt’s recent revolutions provides Esti with a perspective on the aftermath of the recent uprisings that forced leaders Hosni Mubarak and Mohammed Morsi from power in 2011 and 2013, respectively.

“Right now, Egypt is frustrated. They thought that they could have a revolution and one year later everything would be perfect and all the problems would be resolved. Instead, they find that cultural and infrastructural changes take decades. They don’t happen right away.”

Through the center, Esti also established a small restaurant that serves food from different countries that is open to all faiths. It is here where food of African, European, Asian, and Latin American origin—Esti likes to cook himself and prepares homemade tortillas—is sold to hungry patrons.

The restaurant is “open to Christians and Muslims, open to diversity,” the priest explained, “to let people meet each other in a safe, respectful environment so they have an opportunity to go beyond stereotype.”

Intellectual Honesty

Esti’s experiences at CGU—particularly while working on his dissertation examining the Gospel of John and the concept of theodicy (reconciling God’s goodness and justice in view of the existence of evil and suffering in the world)—provided their own valuable lessons.

“What I learned is that in order to write a good dissertation, you have to be your own best friend and your own worst enemy. You cannot compromise on the truth. You have to be very excited about what you think is good, but then you have to step back and try to be the devil’s advocate and say, ‘Let’s see if we can deconstruct or see this in a different way.’ So that intellectual honesty was really shaped at CGU.”

His time in Egypt will end in a few years. He plans to leave the country in 2017 and return to the United States for a sabbatical. Later, he may teach theology or continue promoting interfaith dialogue.

But Esti knows he will continue his work in social development.

“I truly appreciate the fact that when you do what you like, what you have a passion for, it becomes much easier,” he said. “It may look challenging and difficult to others, but to me who felt a passion for it, it was something I wouldn’t want to change for anything else.”

St. Daniel Comboni

In the nineteenth century, Italian priest St. Daniel Comboni journeyed to Africa with priests and lay people from all over Europe where he would found the institution that would become the Comboni Missionaries. Guided by the motto “save Africa with Africa,” Comboni Missionaries have the threefold goal of ministering to the world’s poorest, helping to improve their quality of life, and preparing them to become evangelists themselves. Now present in over 40 countries with over 4,000 members, Comboni Missionaries focus its domestic work on raising missionary awareness and ministering to minority Catholic parishes, and internationally continue to evangelize and set up schools at every level to teach communities in Europe, Africa, North America, South America, and Asia to become evangelists themselves.