Diabetes Free Riverside: Preventing Disease

It was the 1970s and Finland had a major problem.

The residents of the industrialized nation had a huge appetite for whole milk, salt, and cigarettes. Eating fruits and vegetables was not common practice. Years of such bad habits were proving deadly. Finns—especially men—were literally dropping dead of heart attacks at an alarming rate.

Faced with the highest rates of cardiovascular disease in the world, public health officials, local groups, and government agencies launched an ambitious effort in 1972 in the rugged eastern region of North Karelia. The North Karelia Project was a multipronged approach that promoted healthy lifestyles by involving schools, community centers, and health services, taking into account the culture, economics, and environment of the region.

The results were startling.

Over time, project officials succeeded in changing the habits of an entire community—and eventually the whole country. By the early 2000s, heart disease rates among Finnish men had plummeted.

A similar effort in the United States—the Midwestern Prevention Project—was successful in significantly reducing substance abuse in Kansas and Missouri. Andy Johnson, professor and founding dean of the School of Community & Global Health (SCGH), was involved in both projects. Their results are clear: a comprehensive, community-based program can dramatically improve public health behavior.

Johnson and SCGH are leading a similar approach to confront obesity and Type 2 diabetes in the working-class communities of Riverside County.

“Lessons learned from the North Karelia Project and Midwestern Prevention Project about the necessity of highly coordinated multi-pronged approaches to prevention are just as relevant to obesity and diabetes control as to heart disease and drug abuse prevention,” he said.

The school is taking an integral role in Diabetes Free Riverside (DeFeR), a diabetes and obesity prevention partnership between CGU, Riverside County, and the Community Translational Research Institute.

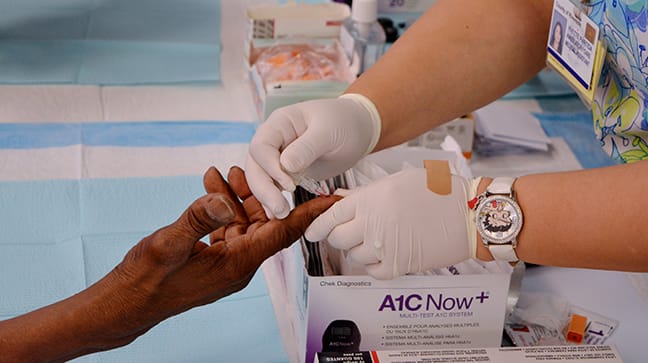

The effort is focused on the cities of Jurupa Valley and Perris and will target their populations over a three-year period. DeFeR will include screenings for diabetes and other chronic-disease health factors as well as interventions at the individual, family, school, and community level. Working in unison with academic, public health, medical, and other organizations, the program will promote lifestyle changes and healthy behavior.

“The strategy includes four outcome objectives: better nutrition, increased physical activity, weight loss, and avoidance of tobacco smoke exposure,” Johnson said.

Participants in DeFeR include students and faculty from SCGH, as well as other institutions such as the University of La Verne, UC Riverside, and Keck Graduate Institute.

The DeFeR effort is loosely based on the models established by the North Karelia Project and the Midwestern Prevention Program, Johnson said.

The North Karelia Project, promoted via town meetings, health centers, and schools. From 1970 to 1995, heart disease deaths had dropped by 73 percent in the region—which at one point was experiencing 1,000 heart attacks a year—and by 65 percent across Finland, according to the World Health Organization. Similarly, abuse of alcohol, tobacco, and illegal drugs was reduced significantly under the Midwestern project, which worked with parents, teachers, and the media.

During the early 1980s, Johnson served on a North Karelia Project advisory committee for youth programs and collaborated with Finnish officials on research. He also assisted the National Institute on Drug Abuse in developing a new funding initiative that came to support the Midwestern project.

Plans call for expanding the DeFeR program to include the Loma Linda University School of Public Health and local nursing programs.