Student Research: The History of Christmas Lights

By Kerri Dean

Kerri Dean completed her master’s degree at CGU in 2015 and is currently a doctoral student in the history department. Her master’s thesis, “Christmas Lights in America: The Intersections of a Modern Christmas, American Culture, and Postwar Suburbia,” focuses on the history of Christmas lights and their importance to American culture throughout the twentieth century.

The turkey is long gone and the dishes have been put away. As Thanksgiving blends into the background of the winter holidays, ornate displays of Christmas lights illuminating neighborhoods, city streets, and shopping centers have arrived. But when did the American tradition of Christmas lights start and who is responsible for it?

The concept of light during winter reaches into many religious traditions. Lighting Yule logs during the dark December solstice dates back thousands of years. The winter solstice is an age-old celebration of light. Druids, pagans, and others have celebrated the return of light long before electric light.

Candles have long been associated with winter holidays of different religions—from the lighting of the menorah during Hanukkah and the kinara in Kwanzaa celebrations to early German Christians who placed candles on the branches of evergreens to resemble the starlight reflection on the winter trees.

But often when we think of holidays and lights, we think of twinkling or colored lights of different shapes and sizes. This modern, Americanized use of lights during the holiday season centers, of course, on the invention of electricity.

Thomas Edison is synonymous with electric light, but he doesn’t get the credit for Christmas lights. The Father of Christmas Lights title is bestowed upon Edison’s business associate, Edward Johnson, who electrified the first Christmas tree with lights in 1882. The New York Times and publications around the country reported on the dazzling beauty of Johnson’s rotating, electrically-lit tree.

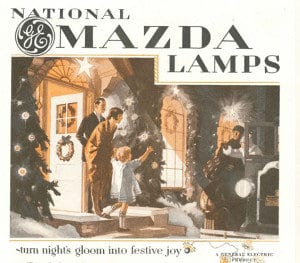

In 1890, Edison sold the light bulb to General Electric (GE), which commercialized the Christmas light. These first bulbs were heavy and bulky and had to be individually attached to a wire on the tree. Only eight bulbs could be attached to a wire.

By 1900, the first advertisements for electric Christmas lights hit consumers, but few could afford the luxury. The majority of America still lived without electricity. At the time, it cost up to $300 to wire a home. The yearly median household income was just $750, so the new rage was limited to the wealthy.

Rich families hosted Christmas tree parties to show off their fancy, lighted trees. These parties were exciting social events for the youth of high society.

As wiring techniques improved—and became weatherproof—the industry grew. New technology allowed more bulbs per wire.

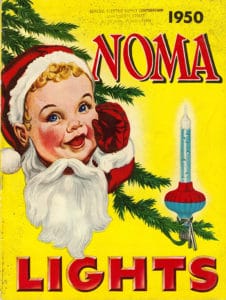

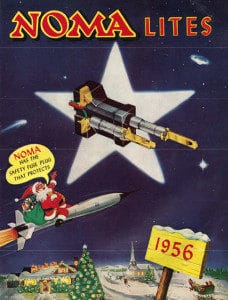

Albert Sadacca, who started selling Christmas lights at his family’s company in 1917, created the “tachon” connector in 1925. It allowed several series of paralleled-wired lights to be connected together. Sadacca realized the potential, but knew his own limitations and reached out to other companies to form a trade association. By 1927, 15 companies emerged under the National Outfit Manufacturers Association (NOMA) name. NOMA (the trademark is currently held by Illinois-based Inliten, LLC), working along with light bulb suppliers General Electric and Westinghouse, dominated the Christmas light industry until the 1960s.

By the 1930s, except in rural areas, most homes had electric lights for everyday use.

“All the world’s a stage at Christmas and all the people on it are lighting prospects,” exclaimed a General Electric ad, as companies seized on the potential of unlimited decorating possibilities and began marketing the lights as necessities of the holiday celebration.

The industry saw a 59-percent increase in sales from 1935 to 1936.

General Electric opened Nela Park, its company headquarters, in Cleveland, Ohio, to demonstrate the possibilities of outdoor lighting. Meanwhile, in Southern California, lights began to make their way on to the exterior of houses. In 1920, Altadena’s Christmas Tree Lane became the first street in America to light up for the holiday season.

Celebrities helped popularize the trend. Silent film star Mary Pickford made it her personal mission to decorate the outdoors throughout Southern California for Christmas in the 1920s through 1940s.

Community trees also showed up more frequently outdoors. The famous Rockefeller Center Christmas tree first appeared in New York in 1931. Within two years, the tree was lit annually as a civic celebration.

As Christmas lights evolved, so did their accompaniments. From tinsel and glass blown ornaments to plastic stars on top, decorations also transformed the Christmas tree. Soon, lights and decorations began to merge, and in 1935 GE sold candle-shaped lamps.

And then, the world went dark.

No lights were manufactured during World War II. Many homes went without electricity for the war effort. Along the West Coast, mandatory lights out for shoreline safety dimmed the use of Christmas lights during the war years.

When the war ended, a new sense of prosperity and mass suburbanization occurred, and Christmas lights had a new meaning. They were mass-produced (and mass-consumed) more than ever before.

In 1946, NOMA introduced its famous Bubble Lights, which became a fashionable decoration well into the 1960s. Other styles continuously emerged, from twinkling lights to globe-shaped bulbs. In 1959, the aluminum Christmas tree popularized the concept of permanent and reusable artificial trees, launching the industry into a new era.

The 1970s energy crisis pushed the industry further into revolution. Lights were increasingly manufactured outside of the United States, and new technology made them more efficient. Throughout the 1970s to today, the design and technology continues to change. Bubble lights and candle shape are no longer the fad. Now strands of artificial icicles and blowup characters dominate front lawns.

Though Christmas lights are now cheap, ubiquitous, and no longer the sole domain of the wealthy, they are still a display of social status. Neighbors compete to outdo one anothers’ ostentatious displays.

Today’s most sophisticated setups sync lights to music to create a visual and audio experience. The ABC television network even launched a reality television show to capitalize on the phenomenon. “The Great Christmas Light Fight” pits families against each other to see who can create the most elaborate displays, with the winner collecting a $50,000 prize and a holiday-themed trophy.

Commercialism, marketing, and reality TV aside, it’s hard not to enjoy Christmas lights.

They’re an American tradition that means more than just climbing a ladder and stapling strands of lights on to a house. They serve as the foundation of childhood memories and help give a continuous cultural meaning to an invention from over a century ago – the light bulb.

So, thank you, Thomas Edison, for the light bulb, but mostly, thank you, Edward Johnson, for deciding to light up your family Christmas tree and giving us a new prism of electric light.