Biomythography: Currency Exchange

There is the show, and there is the preparation. The first welcomes the public to observe your art, unravel it, judge it, and in the most flattering, sensual sense of the ambiguous word, “experience” it. The second, as in the creation of art for a gallery exhibit, is a bit like drawing life from dust.

“Installations are tricky,” says artist and Claremont Graduate University (CGU) alumnus Chuck Feesago (MFA, 2007). Describing his process, “A lot of work occurs in model form, just to determine the possibilities within the framework of the idea,” he said. “Then comes the engineering of the parts to make sure of its stability concerns. Then, the actual installation. Much is added and changed and progresses as I see how I relate to the work in the space.”

With that said, the physical construction of an installation, such as the one Feesago’s creating for CGU’s first fall exhibition, Biomythography: Currency Exchange, takes Feesago about two months. But the conceptual mode, he says, can mentally stew for up to half a year. All that work for essentially a one-off—a custom-made installation inspired by the specific conversations around the show, never to be shown again. And yet artists across the world do it, without much caring whether the viewer “gets it.”

“The work I present is more of a question,” Feesago says. “I am more interested in having the work trigger memories, awareness, reflections of their own stories. Did I cause them to remember? Did I cause them to feel? Did I cause them to reevaluate their perspective?”

Biomythography: Currency Exchange, which runs August 29 through September 16 at the East and Peggy Phelps Galleries, is CGU’s first art exhibition for fall 2016.

Feesago will be joined by other emerging, contemporary artists from the United States and Latin America who are creating pieces connected to “biomythography,” a literary term that already has inspired three prior exhibitions. All the exhibitions—including this month’s—were co-curated by CGU alumna Jessica Wimbley (MA, Arts Management, 2013) and Chris Christion, manager of the East and Peggy Phelps Galleries.

And here, there are several points worth pausing for. As CGU’s first installation for 2016-2017, students will see the gallery in its primary context: as a valuable space to showcase their own work, as well the work of established artists outside of Claremont. And then there’s the reality that the Biomythography series—though not something you’ll find trending on Twitter—is gaining traction within art circles. So CGU’s hosting of such an exhibit supports the term’s growing identity and relevance.

“The more exhibitions, programming, and lectures we do,” Wimbley says, “the more Biomythography spreads.”

In 2014, the Biomythography show Wimbley and Christion co-curated coincided with the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Reading. These thoughtful couplings of art-meets-art-and-academia provide opportunities to augment and complement existing programming, build stakeholders in your exhibitions or projects, or create a tone of collaboration rather than competition, Wimbley says.

“What’s great about working on an interdisciplinary project like Biomythography are the number of opportunities for connections and synergy across fields and different organizations,” she said.

The term “biomythography” is a literary one, defined by warrior poet Audre Lorde as “combining elements of history, biography and myth.”

In its application to art, we “are taking [Lorde’s] definition, and investigating it as an interdisciplinary visual art practice,” Wimbley says. “It actually helps artists by providing a richer language in articulating and contextualizing their work. It connects artists and artworks with ideas in other fields: critical race studies, literature, poetry, media studies, gender studies, performance studies, education, science—the intersections are quite extensive.”

Wimbley first introduced the concept to photography students she was teaching at Chapman University. “The term really resonated with them, which lead me to believe there is something to its relationship to the visual arts.” From there, she says, “the curatorial project started to evolve. “We are able to introduce the term and ideas to international artists and be in conversation with artists working in Southern California. It’s been incredible.”

Feesago is among them. (See full list, below.) For the last decade, he’s been an adjunct professor at the University of La Verne, where he serves as manager of the art and art history department studio. That’s where he first met Wimbley, who was there for a residency. In conversations, the pair learned more about each other’s practices and how some of the issues they addressed coincided.

“One common factor was our multicultural existence, and how our perceptions informed our work,” Feesago says. Co-curator Christion is someone he’s known since Christion’s graduate days at the University of California, Irvine.

In pursuing artists for this venue, Wimbley and Christion considered aesthetics, process, and content across their body of work, rather than for a singular piece. They visited exhibitions and artists’ studios online and in person. Says Wimbley, “We sought artists who not only fall under the theme of ‘biomythography,’ but whose works provide an essential element to the conversation—visually, conceptually, and between the different artists in the show.”

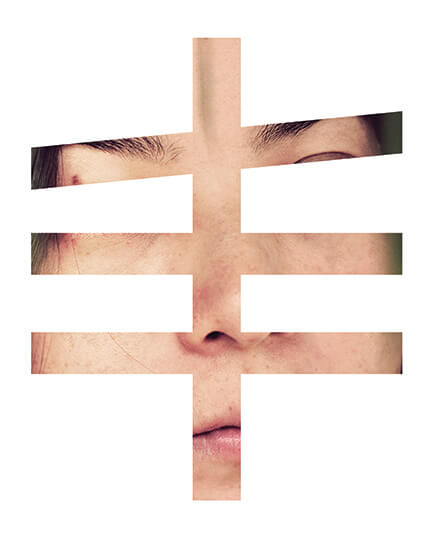

Feesago’s work, she says, is layered and nuanced. “He has a strong history of making compelling, temporal installations that speak to the domestic tensions between cultural, shared, and individual memory, and the performance of identity through architecture/sculpture.”

For the show, the CGU alumnus will erect an installation that he says addresses the “filters” that shift, modify, enhance, and destroy culture. “For me,” Feesago says, “culture does not rely heavily in the past, but thrives in social interaction of the present—where the past is only a thread that can be fragile and break, or strong and guiding.”

It was his CGU education, Feesago says, that gave him confidence to pursue his practice on his own terms, “and not worry if I didn’t succeed in the traditional sense.

“Having gallery representation, selling artwork, doing museum shows, etc.—all those things are great,” Feesago says. “But they’re often limiting when it comes to producing unconventional work, and the need for flexibility within one’s practice.”

Feesago’s work is joined by the following artists: Guillermo Bert, Audrey Chan, Christian Salablanca Diaz, Mimian Hsu, Albert Lopez Jr., Elisa Bergel Melo, Kimberly Morris, Marton Robinson, Javier Esteban Calvo Sandí, and Glen Wilson.

A public reception will be held from 6 to 9 p.m. on Tuesday, August 30.

“The response from other artists, academics, and institutions has been the most impressive,” Wimbley says. “In some cases, artists are being introduced to Audre Lorde for the first time, and her name has become connected to the visual arts.

“CGU is an institution that values and promotes transdisciplinary learning in an academically vigorous environment,” Wimbley says. “Coupled with a gallery space that encourages experimental curation, and intellectually challenging exhibitions, these make it a good fit for us. And the campus community benefits when exhibitions are a catalyst for collaboration and conversation across fields.”