History of Helping

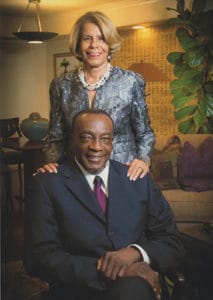

Philanthropists Matthew and Roberta Jenkins cultivated 30 years of giving and sharing

In 1886—more than two decades after the Civil War ended—16-year-old John Wesley Jenkins was beaten up by the Klan. He was abducted, tossed into a train, and later left to die by the side of railroad tracks miles away from his Mississippi home.

But he survived. Nursed back to health by Greek immigrants that found his near-lifeless body, Jenkins later bought 40 acres from them and started a new life in Alabama. John Wesley Jenkins became a prosperous farmer, a respected community member, and a proud husband and father of 10 children.

A sudden heart attack struck him down at age 62. But his wife, Amelia, and children—including then-two-year-old Matthew Jenkins—were left with his legacy.

“I always thought I knew my dad, and all the things that I was told about how much he was respected by everybody,” said Matthew Jenkins, 82. “So, although he was not present, physically, in my mind—the way the neighbors would explain his values to me; his hard work, his honesty, his integrity—I knew that he was the kind of person I wanted to be.”

This emphasis on hard work, discipline, and setting goals remains strong for Matthew and his wife Roberta. Through their leadership and philanthropy, they have proudly served as two of CGU’s strongest supporters for nearly 30 years.

Great Plans

The 40-acre turpentine farm John Wesley Jenkins purchased expanded into a thriving 1,052-acre enterprise. He was one of the first to use tractors and other modern farming methods. The farm was also equipped with a distillation plant to convert pine tree rosin into turpentine and a sugar cane processing operation.

John and Amelia Jenkins’ bountiful harvests of sweet potato and other crops were some of the biggest in Baldwin County, and were written up in the local newspaper.

But it was never just about financial success.

The couple built more than two dozen homes for their farm workers. Amelia and her daughters would drive a truck loaded up with food into the fields at lunchtime to help their workers.

“We did so much for people,” Matthew Jenkins recalled. “One day, I asked my mom, ‘Why do we do so much for other people?’ She looked at me and said, ‘I hope one day you will understand.’ That’s all she said.”

When John Wesley Jenkins passed away in 1935, Amelia was pregnant with their 10th and last child, a daughter. Notwithstanding, the family farm continued to thrive. All the children pitched in—their parents never believed in excuses.

“You always wanted to carry your part of the load,” Matthew said. “My brothers and sisters would compete all the time. We’d compete to see who could pick the most potatoes. We’d compete to see who would be the best.”

By the time Ebony published an article on the farm in 1953, the magazine described them as “Alabama’s Richest Farm Family.”

After considering remaining at the farm—an option his mother discouraged—Matthew decided to attend Tuskegee University, where three of his siblings were already attending. He chose to study veterinary medicine because his brothers told him it was the university’s most difficult subject.

“I always liked a challenge,” he said.

After receiving a doctoral degree in veterinary medicine in 1957, Jenkins conducted research and later established a rabies eradication program in Greenland while serving in the U.S. Air Force. He established a successful veterinary practice in California and sold it in the late 1970s to pursue other career interests such as the import-export business and banking. He and Roberta—they had met at Tuskegee—also created a successful real estate and property management company.

He is currently in the third phase of his career: university philanthropy.

Holistic Education

The Jenkinses have supported education for decades.

They established the Matthew and Roberta Jenkins Family Foundation in 1984, which provides scholarships for African-American students, including those at CGU.

In the 1980s, then-CGU President John D. Maguire, a civil rights activist and former colleague of Martin Luther King Jr., approached Jenkins and asked him to serve on the board of trustees. He ended up serving on the board from 1989 to 2006. Starting in 1995, Roberta Jenkins served on the School of Educational Studies’ Board of Advisors for 20 years.

The Jenkinses also provided funds to launch the Claremont Long Beach Math Collaborative, a partnership between CGU, Harvey Mudd College, and the Long Beach Unified School District to provide math education for underserved communities, especially African-American high school students. They remain involved, serving as speakers, recruiting African-American leaders to serve as role models, and encouraging community members to contribute.

“Education is holistic. It’s not just what’s between two book covers,” Matthew Jenkins said.

The Jenkinses also created a charitable trust that provides fellowship support to African-American students enrolled in doctoral and master’s programs at the Drucker School. Drucker’s Jenkins Courtyard is named for them.

We Give, We Share

More recently, the Jenkinses were the largest contributors to CGU’s Black Scholars Award, founded last year by then-SES doctoral student (now alumna) Calista Kelly. Kelly said she was inspired by the couple, particularly Matthew’s commitment to education.

“Something valuable he talked about was the value that knowledge has because it is something others cannot take from you,” she said. “They cannot take away your education and your drive and will to succeed.”

Currently, Matthew Jenkins is finalizing his autobiography, to be published later this year. Titled Positive Possibilities: My Game Plan for Success, the book will detail the experiences and lessons that have propelled him over the years.

Sharing success remains a lesson deeply ingrained in his lifeblood.

“That’s who we are, we help other people,” he said. “We give, we share. It’s part of my heritage.”