Out of Egypt

Why is the study of Coptic heritage deeply connected to CGU?

This past summer, a major scholarly event celebrated the university’s rich ties to one of Christianity’s oldest branches.

7,470 miles.

That’s the approximate distance between Alexandria, Egypt, and Claremont, California.

As great as that distance seems, a strong thread runs between the two places, and has connected them for more than 50 years.

Since the 1960s, Egypt’s Coptic heritage has enjoyed a second home at Claremont Graduate University—a special relationship celebrated this past summer during the 11th International Congress of Coptic Studies.

“It is through a great partnership like this one that academic study flourishes and human development progresses,” said Ambassador Lamia Mekhemar, Consul General of the Arab Republic of Egypt, on the opening day of the July 25-30 event. “CGU has always been a solid partner in the preservation of our cultural heritage.”

the lecture rooms of the

Burkle Building for a week

of exciting discussion on

the Coptic past, present,

and future.

A major scholarly event occurring—like the Olympics—every four years at a chosen university reputed in Coptic studies, the congress gathers nearly 300 scholars from 24 countries and six continents for a week of panels and discussions on the latest scholarly findings. Topics spanned the spectrum, from Coptic architecture and iconography to the impact of digital technology on the study of ancient manuscripts, hierarchy and leadership in the Coptic Church today, early Egyptian monasticism, and the Coptic diaspora.

Metropolitan Serapion of the Los Angeles Coptic Orthodox Diocese and CGU President Robert W. Schult were among the participants

CGU co-hosted the congress with the St. Shenouda the Archimandrite Coptic Society under the auspices of the International Association for Coptic Studies. Critical to preparations for the event were the university’s own Tammi Schneider, dean of the School of Arts and Humanities and professor of religion; faculty members Gawdat Gabra and Sallama Shaker; 11th Congress Secretary Hany Takla; and S. Michael Saad, chair of the CGU Coptic Studies Council and managing editor of CGU’s Claremont Coptic Encyclopedia.

The last time the congress convened on American soil was in 1992 in Washington, DC.

“Having the congress here on our campus marks a wonderful milestone for us, a reality that surpasses our dreams,” explained Saad. “Our university enjoys a long, fruitful relationship with the members and leadership of the Coptic Church.”

Ancient Tradition

The term “Copts” generally refers to those identifying themselves as the Christians of Egypt. According to tradition, the Coptic Church originates in the teachings of Saint Mark, who brought Christianity to Egypt during the reign of Nero in the first century.

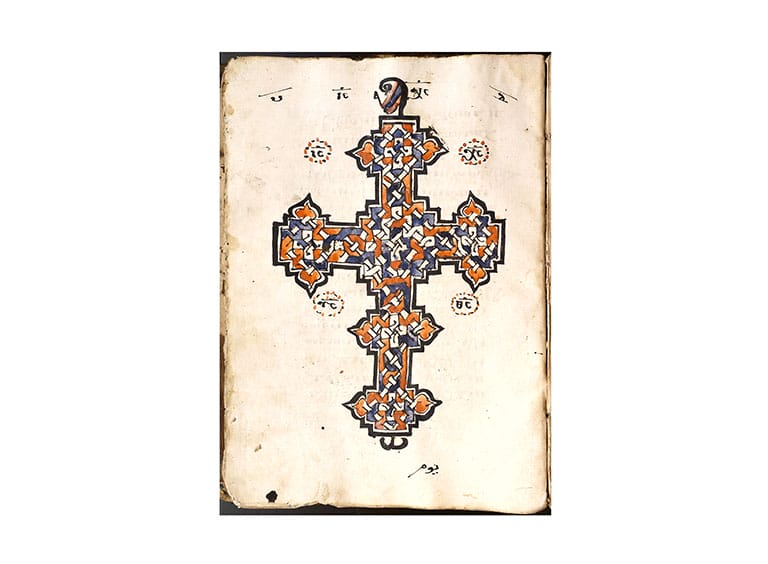

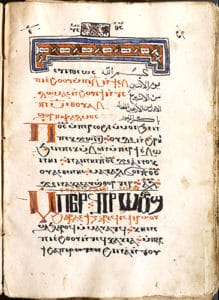

As historical upheaval and change challenged Christianity in that region, the faith and its cultural heritage managed to survive and thrive unbroken in Egypt for 20 centuries. That remarkable endurance record is more than just a source of pride for the Copts—the institutions, art, architecture, music, and writings produced during these centuries provide us with precious insights into the ancient world and the interaction (and frequent collision) of creeds and cultures as empires rose and fell.

As historical upheaval and change challenged Christianity in that region, the faith and its cultural heritage managed to survive and thrive unbroken in Egypt for 20 centuries. That remarkable endurance record is more than just a source of pride for the Copts—the institutions, art, architecture, music, and writings produced during these centuries provide us with precious insights into the ancient world and the interaction (and frequent collision) of creeds and cultures as empires rose and fell.

That region was also the location of a major discovery, in 1945, of the papyri manuscripts known as the Nag Hammadi codices. The cache of Gnostic manuscripts was unearthed near the town of Nag Hammadi (about 50 miles north of the city of Luxor), but its transmission to the world was prevented for many years. Scholars who might have created a richer, fuller picture of early Christianity with this material had no other choice but to wait for two decades.

Enter CGU’s James Robinson.

“Hub of Coptic Studies”

The founding director of CGU’s Institute for Antiquity and Christianity, Robinson played a critical role in translating and publishing these works of early Christianity—which include the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Philip, and the Gospel of the Egyptians—and making them available to scholars worldwide.

On the heels of Robinson’s groundbreaking work, our university’s profile as a hub of Coptic studies flourished:

- CGU has grown into a center for translating and publishing ancient Coptic manuscripts dating to Robinson’s establishment of the Coptic Gnostic Library Project.

- One of the first textbooks for learning Coptic grammar was produced in Claremont.

- CGU has offered courses in Coptic studies since the 1970s.

- Coptic heritage entered the digital age with the online Claremont Coptic Encyclopedia.

- In fall 2015, the university welcomed a visit by His Holiness Tawadros the Second, Pope of the Coptic Church, on the opening of a Coptic school at the Claremont School of Theology.

The congress was accompanied by The Legacy of Christian Egypt, an exhibit of ancient papyri and other manuscripts at the university’s East and Peggy Phelps Galleries that was sponsored by CGU, the St. Shenouda Society, and Washington D.C.’s Museum of the Bible.

James Robinson’s Legacy

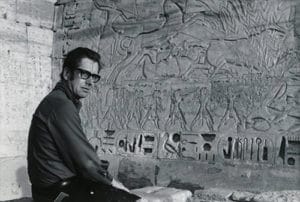

An emeritus professor of New Testament who first joined the Claremont School of Theology in 1958 and moved over to CGU in 1964, James Robinson played a central role in illuminating early Christianity and, in particular, breaking a 20-year monopoly on the Nag Hammadi collection that kept these ancient works out of sight.

Collections, Claremont

Colleges Library.

The prominent scholar died in March 2016. He was 91.

Despite his passing, Robinson’s presence was still felt during the congress—in panel discussions about the Nag Hammadi effort as well as in “James M. Robinson and the Nag Hammadi Codices,” part of The Legacy of Christian Egypt. This exhibit honored Robinson’s tirelessness, his many roles—as writer, translator, archaeologist, explorer, negotiator—and his prodigious contributions to the study of the Nag Hammadi manuscripts, the historical Jesus, the Sayings Gospel Q, and more.

Similar tributes were given during a reception in Robinson’s honor.

Professor Stephen Emmel, a former CGU student who is a professor of Coptology at the University of Münster in Germany, described Robinson’s generosity. He told a story of how he once wrote to Robinson about his interest in the Gnostic manuscripts. Not long after he sent his letter, a bulky package arrived on his doorstep. Not only had Robinson promptly answered him, he had sent along copies of the Nag Hammadi texts to Emmel—a humble graduate student at the time—to examine! Emmel went on to study with Robinson and serve as his research assistant in Egypt.

The gesture demonstrates not only Robinson’s generosity but also his commitment to scholarly knowledge that is sometimes kept away from public view.

In his own books—The Nag Hammadi Story and The Secrets of Judas—Robinson chronicled the circumstances that stalled the public appearance of the texts he studied as well as his characteristic disdain for profit over knowledge, writing that “what has gone on in this money-making venture is not a pleasant story—about how all this has been sprung upon us, the reading and viewing public—and you have a right to know what has gone on.”