Honoring the Visionary Art and Inspiring Mentorship of Roland Reiss, 1929-2020

WHEN HE WAS ASKED in a 2018 HyperAllergic interview to talk about his artistic career, Roland Reiss described his ongoing efforts to push the envelope and discover new things.

“I have seen art as an adventure in which one discovers new territories,” the acclaimed artist and CGU emeritus professor said. “One finds one’s authentic voice in each new challenge.”

But being an adventurer, he added, could be a little problematic, too.

“I think I made a habit of doing what you were not supposed to do,” he said. “It did make it a lot harder, but I had no choice.”

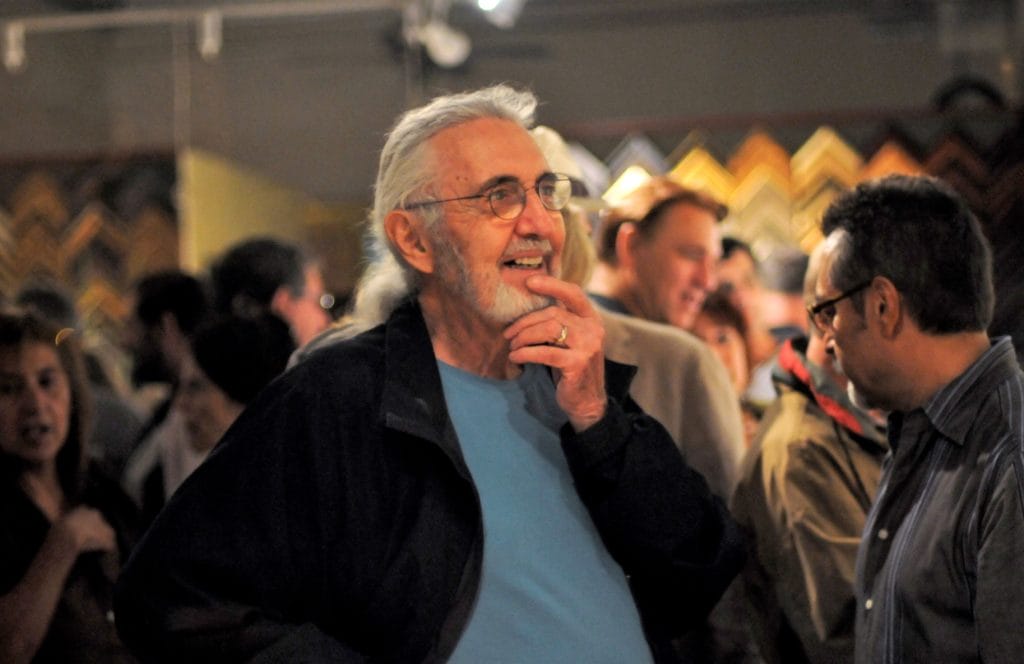

Many in the CGU community and art world are mourning Reiss’s passing, a groundbreaking artist whose continual self-reinvention and envelope-pushing created a vibrant, unique body of work. Widely known for his paintings and creation of intricate miniatures, Reiss died earlier this week of natural causes at his L.A. home and studio at Brewery Artist Lofts. He was 91.

His passing was announced on social media by Reiss’s Los Angeles gallery, Diane Rosenstein Gallery.

“We mourn his passing,” the gallery’s Instagram announcement said, “and offer our sincere condolences to his wife, the artist Dawn Arrowsmith; his family; his studio manager, the artist Jorin Bossen; and his extended family of colleagues, artists, and students at Claremont Graduate University.”

A tremendous outpouring met that announcement on social media from many of Reiss’s colleagues, friends, and former students. A sampling of Instagram posts offer:

- “So sad to hear this. He was the most important teacher I ever had. Our studio conversations from CGU and after still ring around in my head. He will live forever in the memories of us all.” ––Greg Rose (MFA, ’97).

- “A great painter and beloved teacher.” ––Quentin Bemiller (MFA, ’07) in an Instagram post with a photo of him and his young daughter visiting Reiss’s studio in 2015.

- “A terrible loss. Roland was a mentor and friend and inspired me in so many ways on my art-making journey. He will be so missed.” ––Cathy Breslaw (MFA, ’06).

Reiss led CGU’s art program for thirty years before retiring in 2002. In an interview this week, Art Department Chair David Pagel praised Reiss for designing an MFA program unlike any other in the nation.

“Everything that sets CGU’s program apart from other MFAs, that’s all Roland,” Pagel said. “He built our program from the ground up, and he gave it such a terrific structure that it really hasn’t changed in the years since his retirement.”

****

Early Years & First Artistic Friendships

BORN IN CHICAGO IN 1929, Reiss moved with his family to Pomona during World War II. He was drawn to the study and practice of art as a young man, and as a teenager, he was introduced to the work of Millard Sheets, who addressed his class at Pomona High School.

Reiss attended the American Academy of Art in Chicago before returning to Southern California to study art at Mt. San Antonio College. When he was drafted into the Army during the Korean War, he continued to work and develop as an artist.

Stationed at Camp Roberts in Central California with combat orders for Korea, Reiss served as the art director for 40 artists working at the base. He painted a mural there that received commendations and won an art prize in a competition that also included fellow artist and soldier Robert Irwin. Reiss believed these successes, and his growing recognition as an artist soon led to the cancellation of his orders to go to Korea.

When his military service was over, supported by the GI Bill, Reiss enrolled at UCLA and met many artists, including Charles Garabedian, Ed Moses, Craig Kauffman, Ray Brown, and James McGarrell. He received a master’s in art in 1956; during his time at UCLA, Reiss assisted the artist Rico Lebrun and studied with William Brice, Jan Stussy, Stanton McDonald Wright, and Anita Deland.

****

Teaching & the Power of Epiphanies

REISS ENTERED THE ACADEMIC WORLD as a senior painting teacher at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

It was there that he began inviting other artists—a practice that was popular with students and that he’d continue at CGU—to teach and work with the students, including Clyfford Still, Richard Diebenkorn, Joan Brown, Nancy Graves, and Hilton Kramer, all of whom became Reiss’s friends.

Gallerist Diane Rosenstein, who has represented his work since 2014, said she was always stunned by his friendships with many of the art world’s significant personalities and Reiss’s own innate humility.

“Roland was friends with so many, but it didn’t change how he treated people. It truly didn’t matter to him who you were, whether you were another artist, a student, or someone he’d just met,” she said. “He was fully attentive and interested in you and what you had to say. There were many times we sat down in his studio and could have talked for hours, to the moon and back. Roland was a fundamentally generous person.”

In the summer of 1966, Reiss left Colorado to serve as a visiting artist at UCLA, along with Diebenkorn. He decided to move back to California permanently in 1971 and headed CGU’s art program for the next thirty years, retiring in 2002.

Reiss didn’t slow down after retirement. In the years after, in fact, he directed Painting’s Edge, a summer artist’s residency for Idyllwild Arts from 2000-2007. In 2009 he received the College Art Association Award for the Distinguished Teaching of Art.

Reiss wanted students to see things on their own. “An epiphany, for him, was way more

powerful than a directive,” says David Pagel.

At CGU, Reiss created a community-centered approach to the grad program, which would earn national recognition under his leadership. What was innovative about Reiss’ design, Pagel said, was that he structured the MFA to emphasize student self-governance, especially in one-on-one meetings with faculty and each student having a studio and an MFA show.

Student self-discovery was essential to how Reiss approached the program and his own teaching.

“I’d get reports back from students about their experiences with Roland, and they were always over the top,” Pagel said. “They’d say how they felt he understood their work better than they did, and that actually helped them to understand their work better, too. That was one of the things about the way Roland worked with students. He was never forceful; it was all about getting a student to see things on his or her own. An epiphany, for him, was way more powerful than a directive.”

CGU honored Reiss’s impact as an artist and educator in 2010 with the creation of the Roland Reiss Endowed Chair, which is currently held by Pagel. Previous chairs were David Amico and the late Michael Brewster. This year, the estate of the late Peggy Phelps, a former trustee and an ardent supporter of CGU’s Art Department, provided an additional $350,000 to enhance the original gift.

****

Flowers, Miniatures & Openness

DURING A CAREER THAT SPANNED SOME 60 YEARS, Reiss exhibited widely and was included in the 1975 Whitney Biennial, documenta 7 (1982), and received fourteen solo museum exhibitions, including The Dancing Lessons: 12 Sculptures (1977) at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

His miniatures, sculptures, and paintings are included in the permanent collections of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), MOCA, The Hammer Museum, The Whitney Museum of American Art, NY; Orange County Museum of Art (OCMA); Palm Springs Art Museum; Laguna Art Museum; and Riverside Art Museum, among others.

In 2014, a retrospective at the Begovich Gallery at Cal State Fullerton highlighted Reiss’s career; that was also the year that Reiss met Bernstein, and together they planned an exhibition to complement the Begovich one.

“He had such an extraordinary presence, such an enormous understanding of art-making,” said Bernstein, who went on to do several more shows with Reiss over the years. “He designed many of his shows on his own, and it was wonderful for my gallery to show his work to younger generations of artists and help them understand his place in art history.”

Abstract Expressionism influenced Reiss’s early work. In contrast, in the 1960s and 1970s, his work reflected the conceptual art movement and the popularity of plastic materials as he explored the human drama with miniature tableaux encased in plexiglass.

“Roland was doing miniatures at a time when representational art was out, when craftsmanship was out. It wasn’t hip or cool to do that stuff at the time, but Roland was a really fearless artist,” Pagel said. “He just did what he needed to do when he needed to do it. And when you look at those miniatures today, they’re really extraordinary. They’ve really held up over the years.”

Reiss’s flower paintings subtly teach us about the mind and human prejudices.

After retiring from CGU, Reiss devoted most of his time to creating a series of floral paintings as a meditation on the impact of color on consciousness. He described this body of work as an effort to “put everything I have learned about painting into a painting.”

These paintings, Pagel said, are extremely deceptive.

“They’re really sneaky stuff,” he explained. “You might see one of them from across a gallery and think, do I really need to look at another pretty picture of flowers? But when you’re up close, you notice things—the colors he’s using are unusual and unlike anything you’d ever see in nature. He’s camouflaged all kinds of things in the paintings, too—buildings, airplanes, people—and all of it has to do with artifice and authenticity. Roland was preoccupied with how our perceptions change over time, how knowledge blossoms over time slowly. That’s our experience of these paintings.”

That experience, he added, can cause us to let go of our prejudices, our preconceived ideas about something—an openness that the world needs now more than ever.

“So much of our culture today is about division, about ‘us vs. them,’ ” he explained. “Roland’s paintings help us realize that this attitude is wrong. His work doesn’t do that in a threatening way, though; it just helps us see that our world is richer, more complex, and nuanced than we thought. For me, that’s what’s really radical about Roland’s work. It’s one of the many reasons we’ll still be celebrating him years from now.”

****

Reiss is survived by his wife Dawn Arrowsmith, an artist who shared Reiss’s life for some 38 years. He was predeceased by his father, Martin, his mother, Louise, his daughter Noel, and his son Clinton. He is survived by sons Adam, Nathan, and Stefan, daughter Talya, stepsons Dan and Jim Nielsen, his sister Marilyn Austin, and eight grandchildren.

The Reiss family plans to hold a celebration of the artist’s life when large gatherings are permitted again.

- Learn more about CGU’s Art Department here