The Trailblazing Life of Pilot, Rancher, and Civic Activist Catherine Vail Bridge

Catherine Vail Bridge (MA, Government 1971) was buried next to her husband at Riverside National Cemetery on St. Patrick’s Day. Art Bridge, who passed away in 2001, flew missions in the Pacific Theater during World War II and commanded a fighter squadron in the Korean War. He served as the California Air National Guard’s base commander in Ontario and later became deputy chief of staff for the Guard, retiring as a colonel in 1972. The California Senate honored him for his service.

Under federal law, a veteran’s spouse is entitled to burial at a national cemetery—but Catherine Vail Bridge was not simply entitled, and she was not just a veteran’s spouse.

She earned it.

Art might never have flown a military plane had Catherine not introduced him to the Civilian Pilot Training Program during their time at UC Berkeley, where they met as students. She had joined the CPTP in anticipation of the imminent war and was almost immediately smitten with flying’s sense of freedom. “Here I was up at 3,000 feet … and looking down I’d see these great big airliners below us that looked as big as toys,” she recalled.

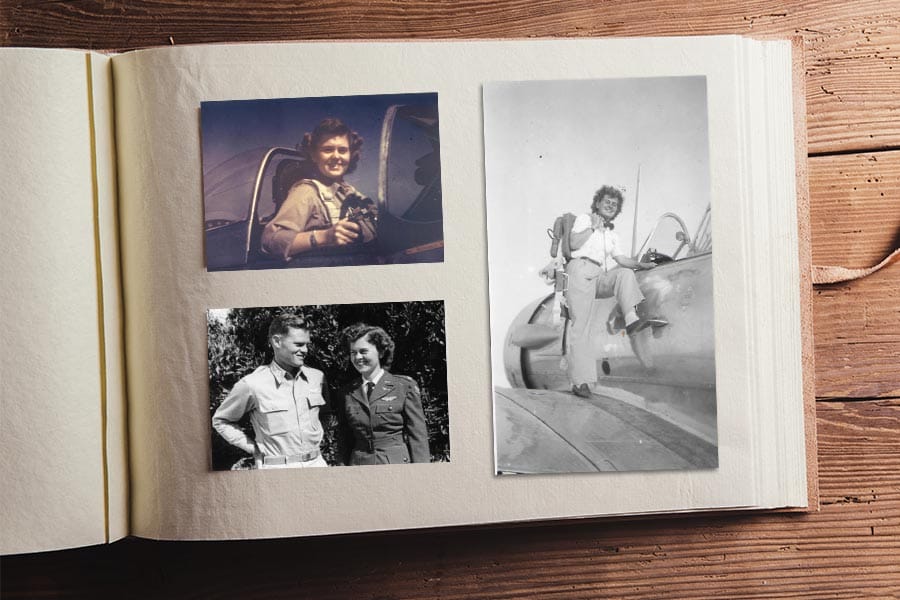

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Art volunteered for the Army Air Corps. Catherine, who possessed a pilot’s license, soon had plans of her own—plans that would introduce her to one of America’s greatest aviators and put her at the controls of 20 different types of military planes. It was a plan that led many years later to her earning the highest expression of national appreciation for distinguished achievements and contributions.

To fully appreciate Catherine Vail Bridge, you need to understand her roots. She was the child of an entrepreneurial family in Oakland that counted the Ghirardellis as neighbors. Her family spent summers at the cabin her father built on the shore of Fallen Leaf Lake near Tahoe. Her mother, Helen Harrington Vail, was an immaculately dressed yet prudent product of the Edwardian era who shopped for clothes two seasons at a time: for the fashions of next year and the year after. But beneath the fashion and social calendar burned a fierce independence. As a child, Helen had dreamed of becoming a pediatrician. With those doors closed to women of her generation, she became a physical therapist instead and taught the profession at an Oakland high school, where she met Catherine’s father.

Catherine inherited that independence.

In the summer of 1942, shortly after graduating from UC Berkeley and with Art in flight training, Catherine received a telegram from her father in Washington, DC that read: “You’d better get out here. There’s a woman recruiting pilots.” Amelia Earhart’s friend and renowned racing pilot Jacqueline Cochran was working with fellow aviation pioneer Nancy Love and General “Hap” Arnold to form what would become the Women Airforce Service Pilots—WASP—a corps of women recruited to fly military aircraft on a variety of missions, including ferrying warplanes from factories to air bases on the US coasts.

Though she didn’t have enough flying time to qualify, she impressed Cochran, who asked Catherine to serve as her private secretary at WASP headquarters in Fort Worth, Texas. A few months later came the chance of a lifetime: Cochran told Catherine that they were going to experiment by training women who lacked the requisite flying time, and she invited her to join the WASP, which had been formed in December 1942. She would have been among the first class to undertake training had her flight to Houston not been delayed. As it was, she was in Class 43-2. Training was stringent and the missions sometimes precarious: Of the more than 50,000 women who applied to the WASP, only 1,830 were accepted, and 1,074 graduated from the training program. Thirty-eight died in service to their country.

Other than combat aeronautics, WASP pilots went through the same training as men. When Catherine graduated in May 1943, she joined the 22d Ferrying Command, headquartered in Palm Springs, and took the controls of whatever planes the military needed to deliver, including the P-38 Lightning, P-40 Warhawk, P-47 Thunderbolt, and her favorite, the P-51 Mustang. She dealt with an engine stall and hydraulic problems, and she carried a .45 pistol on planes that used the Norden high-precision bombsight in case anyone tried to steal the state-of-the-art technology. She and the others in WASP were de facto test pilots in newly developed aircraft on special missions.

Over the next 18 months, Catherine flew more than 1,000 hours—an accomplishment that takes most pilots four or more years to achieve. “WASP proved that women could do the job and do it well,” she reflected. “In the two years they served in the Air Transport Command’s Ferrying Division, they alone made 12,652 domestic deliveries of US military aircraft.”

Then the missions abruptly stopped.

In December 1944, with the Axis powers’ defeat in sight, the Pentagon determined it didn’t need as many civilian flight instructors to train airmen. Rather than thank the returning aviators for their service and send them home, they assigned them to the training function or to delivering the planes. WASP was disbanded, and the women were sent home.

It was “a very demoralizing experience, the absolute worst I have ever had, and one I will never forget,” Catherine wrote in a memoir.

“It was as if they were told, ‘Thank you very much, ladies, you can go home now and do the laundry and wash the dishes and raise the kids,’” her younger son Richard Bridge recalls. “I really think there was a lot of bitterness shared by all the WASP pilots that their skills were not regarded and that women, after having contributed so much, were relegated to their second-class role again.”

Catherine and Art married while they were both home in Ontario on leave from service in July 1944. While waiting for his demobilization from service in the Pacific Theater, Catherine and other former members of the 22d Ferrying Command worked at Gore Field in Great Falls, Montana, helping pilots back from the war to earn their FAA commercial and instrument licenses. When Art returned to Alta Loma in June 1945, Catherine left her life in aviation to rejoin him.

An adventure of a very different sort awaited her.

Much of Southern California in the early postwar years was still rural, including the vast greenbelt of citrus trees that hugged the San Gabriel Mountain foothills and acres of vineyards farther east to San Bernardino. The 22-by-22-foot house that Art and Catherine built in the lemon groves on Banyan Street in Alta Loma became home for them and their growing family—a far cry from the house her father built in the Oakland hills overlooking the San Francisco Bay where she grew up.

Along with his work as operations officer for the 196th Fighter Squadron at Norton Air Force Base, Art assumed the family business of managing the George Newton Hamilton Citrus Ranch that Art’s mother and her siblings owned—double duty that required a capable partner.

The citrus needed tending whenever the temperature fell toward freezing. First, Catherine would check the thermometers throughout the groves. Then, as temperatures dropped below 35 degrees, huge fans powered by V-8 engines had to be fired up to warm the air around the trees. Ranchers of that era might call it men’s work—but the division of labor on the ranch meant Catherine did it.

“Mother had to learn how to start wind machines in the cold and isolation of the country in the dark,” her older son Arthur recalls. “Wind machines are complicated pieces of equipment, but I think her WASP experience helped.”

When it got colder, smudge pots were lit in the dead of night to prevent fruit-killing frost. That was Art’s job, but, after he was mobilized to serve in the Korean War, it fell to Catherine as well, along with tending to young Elizabeth and Arthur, maintaining the home, and running the entire ranch operation.

“My sister—she couldn’t have been more than 5 years old—remembers stroking Mom’s arm to console her. It was a lot of work that she had to learn on the job, and she was responsible to Dad’s family for the ranch while he was in Korea,” Arthur says.

In the 1960s, it became clear that ranch life was winding down. Huge housing tracts were spreading eastward following the San Bernardino Freeway, and the re-zoned property meant that tax burdens skyrocketed. With college over the horizon for her three children, Catherine decided she needed to do something.

“I entered Claremont Graduate School [in 1962] seeking a master’s degree in order to teach,” she said. “The economics of citrus growing did not promise financing for the children’s college education. … I was the only woman in my government classes, and I was so much older than everyone else. I was scared that I wouldn’t have the right answers, the right questions, the right grades.”

Studying under Professors George Blair, Leo Strauss, Douglass Adair, and Harry Jaffa proved to be a transformative experience, and she thrived.

“There were some profound insights that she would bring home and go on and on and on about at the dinner table,” Richard recalls. “The light of intellectual passion was very much alive in her eyes.”

(Arthur and Richard are CGU alumni as well.)

The idea of unifying the communities of Alta Loma, Cucamonga, and Etiwanda emerged in a conversation among a few couples in the Bridges’ living room not long after Catherine had graduated from CGS (now CGU) in 1971. With suburbanization in the region taking hold, a union of the three communities into an incorporated city offered advantages, but there was hardly a groundswell of support.

“Alta Loma was still very much in citrus and Etiwanda in vineyards. Cucamonga was more industrial-commercial,” Richard says. “How do you stitch those three together? It was a real work of persuasion.”

Buoyed by advice from George Blair, Catherine collaborated with fellow Alta Loma resident Marge Stamm to win people over. Catherine served as a founding member of the Tri-Community Incorporation Committee, and Marge was a powerhouse.

“Marge worked in the school district, so she knew every family,” Richard says. “Her opinion was instrumental in moving public opinion toward incorporation.” (He also credited, among others, Lloyd Michael, father of current Rancho Cucamonga Mayor L. Dennis Michael, and neighbor Al Cherbak with vital roles in bringing the communities along.)

Voters of the three communities approved incorporation in November 1977. Art served as the city’s first mayor pro tem. Catherine remained active in civic life as well, working to preserve green spaces in the fledgling city as a founding member of the Friends of San Bernardino County Cucamonga-Guasti Regional Park. When county commissioners attempted to turn a park she had helped create into a law and justice center—a jail—she resisted.

“The commissioners were listening to the pros and cons of that, and Mother comes up to the mic and says, ‘Commissioners, I oppose this because we’ve worked really hard to create beauty and recreation in our city, and should you support this today, I will have 30,000 signatures on your desk by tomorrow.’ She was the director of volunteers and she knew everybody,” Arthur says. “And she didn’t make idle threats.”

The jail was not approved.

The WASP, which was relegated to history in 1944, was finally recognized in 1977 when the G.I. Bill Improvements Act changed the women’s status from civilian to veteran, cementing Catherine’s Honorable Discharge as a first lieutenant in the Army Air Force. In 1984, every WASP veteran was awarded the World War II Victory Medal. And in March 2010, Congress honored WASP pilots with the Congressional Gold Medal, which, along with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, is the highest civilian honor bestowed for courage, service, and dedication.

“That really meant a lot to our mother,” Richard says. “She felt redeemed by the federal government for the way WASP was treated in 1944.”

Catherine Vail Bridge died on December 6, 2022, at the age of 102 and was given full military honors at her burial on St. Patrick’s Day. An honor guard played taps. Seven service members fired three rifle volleys. The eldest sibling, Elizabeth, was presented an American flag with the traditional words of thanks: “On behalf of the President of the United States, the United States Air Force, and a grateful nation, please accept this flag as a symbol of our appreciation for your loved one’s honorable and faithful service.” She also received a signed certificate from President Biden in recognition of Catherine’s service. The celebration of Catherine’s service to her country culminated the Rancho Cucamonga City Council’s honoring her on March 1, and the California State Assembly’s recognition on March 12 for her contribution to the founding of the City of Rancho Cucamonga.

The marker at Catherine and Art’s gravesite bears the most optimistic phrase in flying and serves as their epitaph:

“Ceiling And Visibility Unlimited.”

This story is based on interviews with Arthur and Richard Bridge, and information from the Library of Congress, the Voices of the Golden State oral history project, the Claremont Courier, Southern California Newspaper Group, ABC News archives, and the Winter 2006 issue of The Flame.